Saturday marks 20 years since the September 11 attacks by Al-Qaeda in New York City and near Washington D.C.

But to the people of Chile, thousands of miles to the south, the same date holds an entirely different meaning.

This story takes us back to the XX Century, far away from the Big Apple, Islamists, and to the White House of a disgraced US president.

Land reforms

The land reforms of the 1960s and early 1970s forced hundreds of wealthy landowners to cede vast extensions of unused land.

The reforms established the maximum amount of hectares a person could own (80) and they also meant the end of inquilinaje, an institution that dated back to colonial days in which peasants worked in the countryside for no pay, typically in exchange for food and a place to live.

This period also saw how a growing working-class movement gained traction and started to demand better conditions of life.

Despite efforts by the US to stop it, that led to the election of president Salvador Allende, America’s first democratically elected marxist leader, on 4 September 1970.

His socialist government nationalized industries, copper, expanded and improved educational and health policies, strengthened the land redistribution scheme and set up milk-giving programs, among other initiatives.

It also expropriated private businesses. That particular policy caused protests, political conflicts and internal opposition, confronting rivals and dividing the population.

The aforementioned, plus a 23-day State visit by Fidel Castro, in November 1971, caught the attention of the US government, who had been for some time monitoring this potential “second Cuba” in the region.

CIA

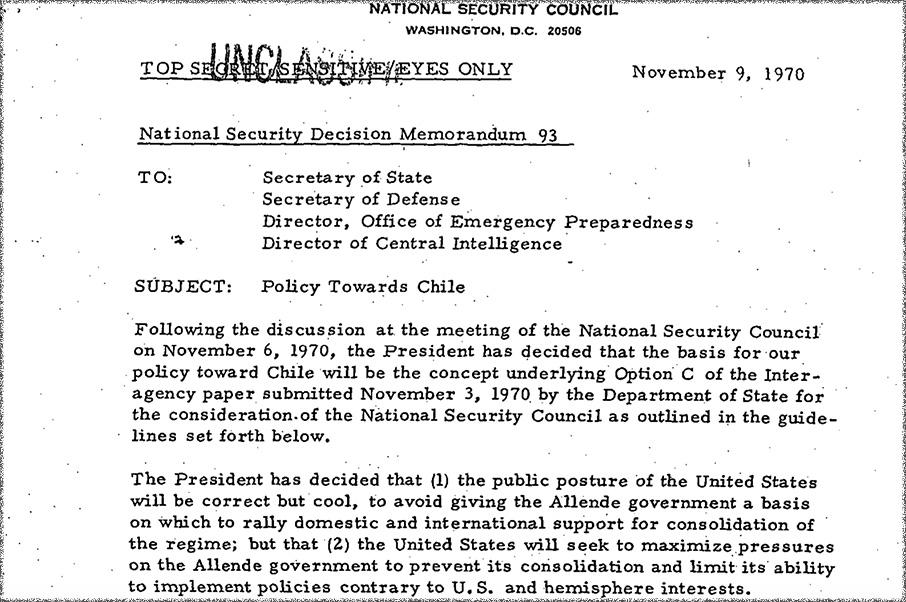

A year earlier, in November 1970, Richard Nixon gathered his National Security Council to discuss the US “policy towards Chile”, a document declassified in November 2020 by the National Security Archive says.

As US interests in Chile were under threat, Nixon acted quickly with the help of his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, who in 1973 was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

“Our main concern in Chile is the prospect that (Allende) can consolidate himself and the picture projected to the world will be his success,” Nixon said in the meeting, the Archive reports.

He then ordered his team to adopt a “hostile program of aggression” to destabilize Allende’s administration, the Archive reveals.

What followed was a CIA operation that involved a multi-million dollar funding effort, fostering right-wing media and appealing to those rich Chileans who were unhappy with the Popular Unity.

Crisis

To this day, the Allende government is a deeply divisive topic in Chilean history. While some still lament his downfall, others rejoice in his demise.

The ideal of a larger State that could participate in the national economy, the increase in public spending and his attitude towards private ownership as well as the upper-classes, traditionally rich landowners, Roman Catholic and conservative, became a recipe for disaster.

Empty supermarket shelves due to hoarding, shortages, the opposition of the unions and weeks-long truckers strikes were finally crowned by a full-blown economic crisis and soaring inflation, 163% by the end of 1972 and 508% in December 1973 (although many believe it peaked at 800%).

But despite the turmoil, Chile went to the polls in March 1973 and the Popular Unity’s candidates to Congress got 43.3% of preferences, blocking the right’s plans to impeach the president and regain control of the country.

Pinochet

That was how the coup d’état to overthrow Allende took shape, with the support and funding of the CIA and the Nixon White House.

El Tanquetazo was the first attempt, on 29 June 1973, a rebellion that was crushed by loyal soldiers under the orders of Army commander-in-chief, Carlos Prats.

But the Armed Forces and the Police succeeded on Tuesday 11 September 1973. La Moneda was bombed and Allende killed himself inside the presidential palace after broadcasting a speech that still resonates with supporters both at home and internationally.

After the insurrection, Gen. Augusto Pinochet seized power. He had been appointed Army chief by Allende in August after Prats resigned following fierce scrutiny in light of his involvement with the Government: he was Home secretary in 1972 and Defence minister in 1973.

In Buenos Aires, on 30 September 1974, Prats was murdered in a car bomb blast engineered by DINA, Pinochet’s secret police.

17-year dictatorship

With democracy in tatters, and the US plans completed, Pinochet ruled Chile with an iron fist for 17 years.

Official figures say that around 200,000 people were exiled, 28 thousand were tortured and over 3,200 were killed. Many were never found.

With no impediments to govern, the US-backed regime transformed the economy with the help of the University of Chicago’s Milton Friedman.

The land reforms were scaled back and the Junta began a massive privatisation process that included companies, the education system, healthcare, social security, natural resources and water.

But after a decade of oppression, Chileans, particularly Pinochet detractors, started to dream of a transition to democracy and some of them resorted to violence.

On 14 December 1983, Pinochet survived an attack by the Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front, a radical left-wing guerrilla.

The following year, on 26 February 1984, Pinochet visited Punta Arenas, in the far south of Chile, where a crowd of people loudly chanted “murderer”.

El Puntarenazo, as it was called, was the first time he faced severe opposition on the streets and the media was there to report it.

From 1 to 6 April 1987, John Paul II visited Chile with “Love is Stronger” as a slogan.

Nevertheless, love was not in the air at the time and the pontiff witnessed first hand the dictatorship’s heavy police repression.

A renowned anti-communist, the Pope was often criticised given that his stance against Pinochet was never truly tough.

With time, centre-left and leftist opponents managed to regroup and started to challenge Pinochet’s power.

Transition to democracy

After years of absolute power, both Pinochet and the Junta were under mounting pressure from home and abroad to put a stop to Human Rights violations.

From simmering, social unrest became patent and the dictatorship was forced to call for a referendum in October 1988.

What was at stake for the regime? The end of Pinochet’s rule through the polls.

Of all people, organisms and countries, the Ronald Reagan White House was instrumental in this period: the US suppported sanctions against Chile, condemned the atrocities of the dictatorship and gave funding for both the National Endowment for Democracy and the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs to observe the plebiscite.

When the day came, 54.70% of voters decided it was time for Pinochet and his Junta to go and on 11 March 1990 president Patricio Aylwin was inaugurated.

New Constitution

In 1980, Pinochet and right-wing lawyer Jaime Guzmán, both admirers of Spain’s Francisco Franco, imposed a new Constitution.

Although amended several times, the Charter still enshrines the neoliberal values Pinochet and Friedman championed.

The October 2019 protests caused a deep social and institutional crisis that allowed for a constitutional referendum to take place.

Only 22% of Chileans voted in favour of keeping the current text.

In May 2021, Chileans elected 155 delegates, with gender parity and indigenous participation, to draft a new Charter.

The left-leaning body started sessions on 4 July and has up to a year to deliver a proposal that will be put to another vote, this time compulsory.

If the Apruebo option wins again, the new document will come into force 10 days after the plebiscite, erasing one of Pinochet’s most transcendent accomplishments as tyrant.

This was a quick summary of a long and complex period of time in Chilean and South American history.

For example, the UK was a part of the effort to stop Allende from donning the presidential sash and funded his predecessor’s campaign, Eduardo Frei Montalva. Australia also played a role helping the CIA with spies.

If you are interested in learning more about this, you can check the following websites:

– Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional

– Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos

– The Chile Documentation Project, National Security Archive

Enviando corrección, espere un momento...

Enviando corrección, espere un momento...